Earlier this month, the New York Times published an article that highlights the disparity between the number of white and Asian students who are identified as “gifted,” and the number of black and Hispanic students identified as such. The article popped up on my Facebook newsfeed this week. It made for a fascinating (albeit alarming) read.

The author, Susan Dynarski, states that, “The numbers are startling. Black third graders are half as likely as whites to be included in programs for the gifted, and the deficit is nearly as large for Hispanics.”

I’m going to assume that Ms. Dynarski’s assertions are accurate, since they passed muster with the editors of the New York Times. If so, this begs the question: what is going on?? Are black and Hispanic kids just not as “gifted”? Seems unlikely.

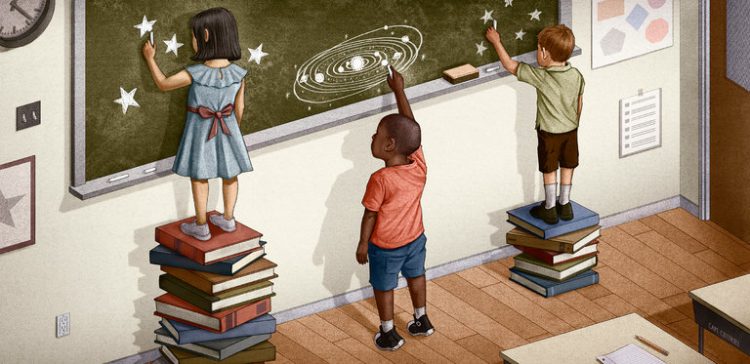

The answer lies in the way students are selected for these opportunities. Many of the programs for students considered “gifted and talented” rely on teachers (and parents) to identify kids who might qualify. The article asserts that schools “have contributed to this problem by underestimating the potential of black and Hispanic children.” (Also, according to the author, the same can be said of students learning English as a second language.)

To substantiate this claim, the author refers to the Broward County School District in South Florida. This school district is one of the most diverse in the nation. More than half of the students are black or Hispanic, and about the same percentage are low income. Back in 2005, Broward County began a universal screening program to identify gifted kids. All second graders took a nonverbal test, with high scorers referred for I.Q. testing.

The outcomes were then studied by the economist David Card of the University of California, Berkeley, and Laura Giuliano of the University of Miami. The numbers tell a story: the share of Hispanic children identified as “gifted” tripled, from 2% to 6%. The share of black children rose from 1% to 3%. Among whites, the gain was less pronounced — from 6% to 8%.

Unfortunately this story does not have a happy ending. In 2010, budget cuts caused Broward County to suspend universal screening. Racial and ethnic disparities reemerged.

Reading this article caused me to really think: Can TORSH Talent, our video classroom observation tool, in any way help rectify the “gifted” disparity issue?

Of course TORSH Talent can’t eradicate all bias in the education system. There’s not one single teacher professional development tool that can accomplish that. But any tool that fosters self-reflection by teachers can only help. Teachers aren’t purposefully overlooking black or Hispanic kids. They just simply aren’t aware they are doing it. And that is where a tool like TORSH Talent can help.

To read the complete New York Times article, click here.